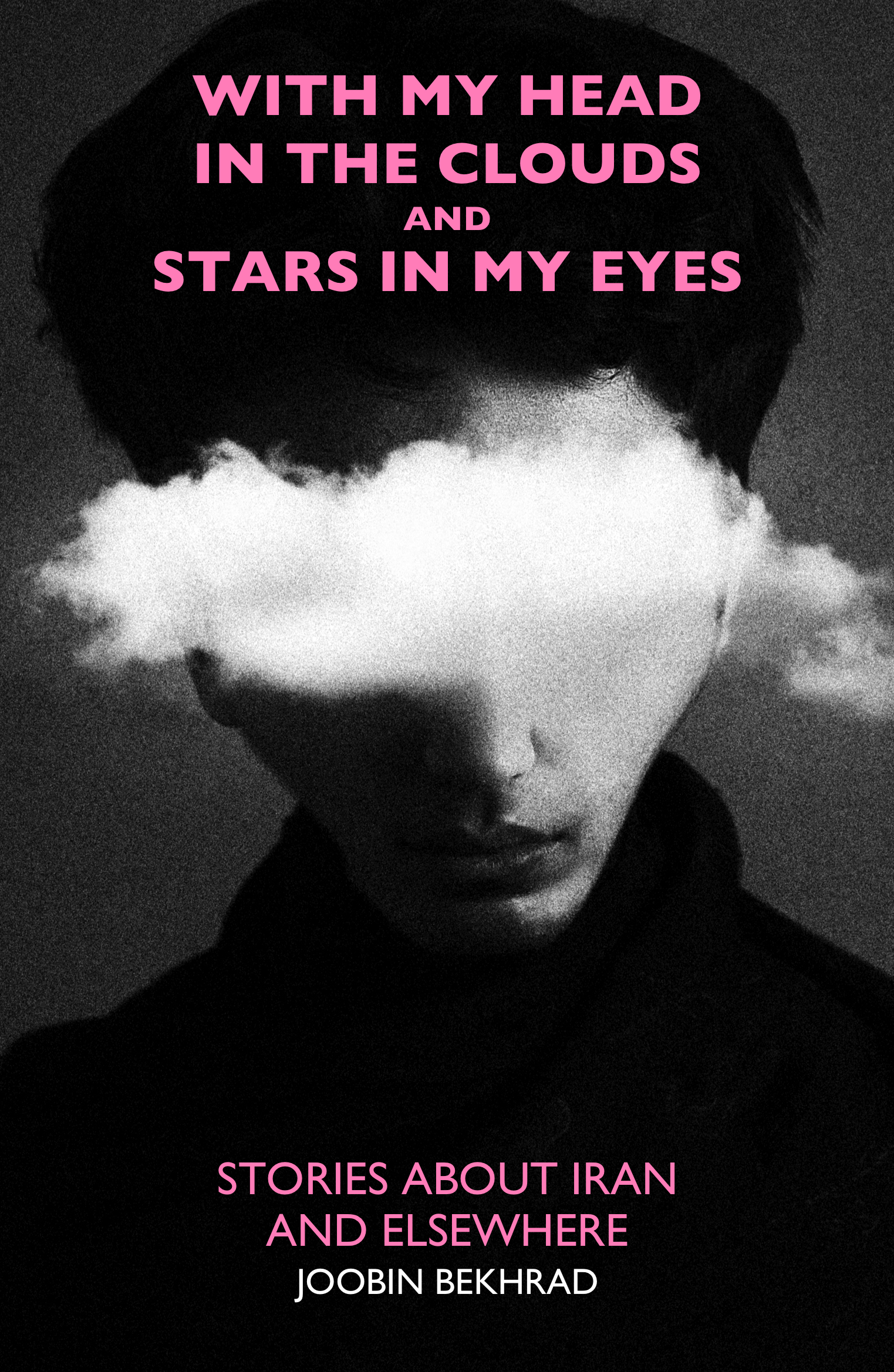

Joobin Bekhrad is a writer and editor who specializes in music, art, literature and Iran. He is the editor of Reorient, a website dedicated to exploring the art of Iran and the broader Middle East. His new book With My Head in The Clouds and Stars in My Eyes is a collection of his stories and essays from Reorient and other places. He kindly agreed to talk to us about his book and his work on Reorient.

Luke: I’d like to start by having you talk to us about yourself and your background.

Joobin: Where do I begin? Well, I was born in Tehran at the end of the Iran-Iraq War. It’s really why we left the country. It wasn't because of the Revolution or anything. My parents actually had a very good life. They would have stayed there if it hadn’t been for me. When I was born, they wanted my future to be certain. You never know with the region, and, even in Europe, you never know what tomorrow is going to be like. We first went to London -we were there for a year- then we moved to Toronto. I’ve been here my whole life. In terms of my education, I studied business administration here in Toronto. Then I did an MSc in management in London at the Cass Business School so despite what people think, I don't have a degree in art history or anthropology or post-colonial studies or anything like that. My background is a business one. My love and my passion has always been for the arts, though.

It first started with music –rock and roll in particular- then I picked up the guitar. I got into literature and other mediums much later. I started really devouring poetry and novels in my first year at university, and visual art kind of came last. I became interested in it not for itself but rather because I was interested in Iran and everything to do with Iran. That’s really where my love for film came from as well, watching Iranian cinema. I just wanted to consume everything to do with Iranian culture. It didn't matter what it was; whether it was cuisine, film, literature and music. So my love for Iranian culture bought about these other passions.

I’m sort of known as a visual arts person. People think that’s really my ‘thing’. I write about many other subjects; actually, and I became interested in visual art at a much later stage in life.

Luke: That's interesting because throughout your book, from the essays you’ve chosen, I would have said that music was your main passion.

Joobin: Exactly.

Luke: It came across very clearly that music was the thing you referred to and wrote with the most passion about. I’m kind of curious, this may seem like a really obvious question but was your interest in Iran and the culture simply because of the family connection or were there other reasons as well?

Joobin: It sort of begins with that. When I was 16, for the first time, I went to Iran on my own. I stayed with people I hadn’t met before. They were the sons of the sister of my father’s business partner. No relation whatsoever. It was kind of a turning point for me. I’d grown up in an Iranian household and I’d been exposed to the language, which I spoke terribly, festivities like Iranian New Year and other ones but I really didn't know that much about the country, the people or the culture. That really changed, the impact showed itself quite soon. That's when I really started developing an interest in Iran. It was because I was Iranian myself, I can’t lie about that, it stems from it but it goes much beyond that. Some people want to physically visit the places they are from and that pilgrimage in and of itself is enough.

In my case, I wanted to know more about myself, my family, my ancestors, my heritage; when it comes to literature and music, though, I also consumed these books and songs for their own merit. But if I was to tell you that my being Iranian didn't have anything to do with this love, I’d be lying.

Luke: I was wondering whether as an expat Iranian you created a connection with your home country through its art.

Joobin: Not so much because it was quite hard to access Iranian literature and art in Toronto so I can’t really say I kept a connection through the arts, but there is quite a large Iranian community in Toronto. Not so much now, but when I was a student or a teenager, it was comforting in a way because I didn't feel the distance so much. Every city has its Chinatown, Toronto has different areas, there is Little Portugal, Little Italy. There is a part of town that is very much Iranian and you really feel that presence there just seeing those signs written in Persian. Even in your car you can smell the food coming out of these restaurants, bakeries and grocery stores. I don't need grocery stores to keep the flame alive but it is sort of … comforting. I can’t think of any other word to express just being in the midst of this presence that’s so tangible.

Luke: Moving onto your book, I enjoyed it and I was wondering what selection process you used for your essays that are included in the book.

Joobin: I’ve dated the essays for a reason, not only to show how my writing style has changed, because it really has, but also these stories were written at very different times over the span of two or three years, and on very different occasions.

I never had the intention to write a book. I realised that in a way that I was working towards a book sort of down the line in around 2015. I started seeing common threads connecting these stories, I could see some continuity and I said maybe I could collect them into a book. That’s when I started thinking something was happening there. After a while penning a few of the really long ones like Children of the Revolution, which was written for a German fashion magazine, or some of the other ones that are lengthier, I started thinking that this will be a chapter of a book. Initially, I had no intention or desire to write a book, they were just standalone pieces; some of them I wrote for Reorient, some of them I wrote for other publications. After a time, I just saw the link between them and thought why not. I’d published two books and was thinking along those lines of what’s going to come next and it seemed natural. Of course I’ve written many more stories. The ones in the book are the most relevant, however, because there are others that were about specific exhibitions or other events that would seem a bit dated if you were to read them now. So I chose the ones that had the most lasting quality.

Luke: There is an interesting range of different topics you touch on, literature to art to music to even noses. All sorts of things are going on there, it’s very nice.

Joobin: Thank you.

Luke: You got it. So, you write about Iran and, of course, in this current situation it’s quite common to hear Iran mentioned in the same breath as countries like North Korea or Zimbabwe and I was wondering if in your work there is an attempt to cast a different light on Iran, to give an alternative narrative to the one you hear a lot in politics at the moment.

Joobin: Definitely, because there is a lot of rubbish being said and ignorance around Iran even amongst Iranians. You’d assume, or maybe you wouldn't, but sometimes you think that by being Iranian the person would know about the rich tradition of visual art in Iran or about New Wave Iranian cinema. There are those historical pieces [in the book] that talk about wine imbibing in Iran, or Iran’s influence on 20th century rock and roll. My audience isn’t only non-Iranians, it’s also Iranians themselves. All these stories are a personal exploration of my heritage, almost like having a conversation with myself. However, I’ve always been compelled by that desire to change attitudes or turn people onto aspects of Iran that they don't really know about and are not often discussed. Iranian cinema gets a lot of attention, I wouldn't be surprised if at a dinner party people are talking about the films of Kiarostami or Farhadi, because they’ve been doing quite well around the world and we are sort of well known for our cinema; but not for other aspects of our history, our culture, or who Iranians are. People still ask me what’s the difference between Iran and Persia, for example. There are also those who think Iran is part of the Arab world and that Persian is like a dialect of Arabic, or that our history starts with Islam and ends with it. There is a lot of ignorance surrounding the country and people.

I don't hold it against people though. You mentioned Zimbabwe; I don't know anything about that country either. I’m quite ignorant when it comes to Zimbabwe, I haven’t really been exposed to Zimbabwean culture or history or anything like that. I think some people are very curious and eager to learn about Iran, which is wonderful; they want to go beyond the propaganda the Western, Saudi, and/or Israeli media is feeding them. Once they read these novels or watch these films I tell them about, they sometimes even go as far as visiting Iran. Their attitudes and mindsets completely change.

Luke: So my next question is something I think about myself when I write. Obviously I write about Turkey mostly and I always worry about the problem of being orientalist. I wonder if it’s something that you worry about and how do you deal with it?

Joobin: Do you mean if I worry about becoming an orientalist myself?

Luke: Yes, or if you’ve been influenced by the backlog of orientalist material.

Joobin: That's a good question. Well, to begin with, I’ve never really agreed with Edward Said’s theory of Orientalism. Some of its tenets, are of course valid but on the whole I think he is guilty of the same crime he accuses the orientalists of: making sweeping generalisations — in this case, about a group of scholars and an academic tradition. Prior to Said, an Orientalist denoted one who studied the Orient, and it only became a dirty word after he wrote the book. In For Lust of Knowing, Robert Irwin tears Said to pieces. It’s very one-sided, but one of the things he argues is that Said fails to make note of so many orientalists who didn't fit the mould. For example in Iran there is the case of Edward Granville Browne who was enamoured with Iran and Iranians and devoted his life to studying Persian literature and he’s got this massive anthology: A Literary History of Persia. In terms of Turkey there is Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. You read her remarks about the Turks and you think she doesn’t fit Said’s bill, so I’ve never really subscribed to that.

Nonetheless, most of the books I read are in English, so I have studied quite a bit of Saidian Orientalist literature. In my piece, Ramblings of an Iranian Wino I quote a lot of these English and French travellers who visited Iran between the 17th to early 20th centuries. I find their work fascinating but I’m reading their works with the right frame of mind, with a deep knowledge of and appreciation for the subject matter at hand. So, for example, let’s say I’m reading the travelogue of a British explorer and he’s making disparaging remarks or he’s making incorrect statements. In many cases many of these books are just littered with mistakes and errors. I still read them and find value in them because there is no danger because I have that background. Let’s say I had no knowledge of Iran or Turkey or Morocco, and I started my research through these travelogues and other such books; in that case, there would have maybe been the danger and risk of becoming a Saidian Orientalist. I would be at risk then of falling to those attitudes or maybe thinking of myself as somehow superior to the people in question because I live in the west and I am somehow culturally superior. I don't know. I don't think I’ve been influenced by any of their attitudes even in the case of the Arab world, Turkey or North Africa. I think there is a danger for those not well-versed in the literature and knowledge of these people, places and cultures. I’d like to think that I haven’t been coloured by Orientalism.

Luke: Thank you, it’s something I worry about myself so I want to see what you thought about it. Moving on, for someone like me who doesn't know about Iranian literature where would be a good place to start?

Joobin: I think the best starting point is The Shahnameh (The Book of Kings), which is an inextricable part of our culture and defines us as Iranians. There are two aspects to it. One deals with ancient Iranian/Zoroastrian myths and legends. The other aspect deals with ancient Iranian history until the Arab invasion. That's a great starting point if you want to understand the Iranian soul and spirit. In terms of other books, perhaps a more recent one, as The Shahnameh is quite old, is a novel called My Uncle Napoleon by Iraj Pezeshkzad that’s available in English. It’s really a great book for anyone who wants to understand contemporary Iranian families, the way we think. If The Shahnameh captures the spirit of ancient Iran, this one captures the sprit of contemporary Iran. It's a hilarious comedy and it was turned into a TV series in the late 70s. That's what a lot of Iranians know it for, when you mention the book they will think of the TV series first. I think no other book captures what it means to be Iranian better than this one. Aside from that, it’s just a fascinating piece of literature, a coming of age novel and there are all these different characters in it. Every Iranian will be able to relate to these characters, they are like stock characters we all know about, they are people we’ve known all our lives and had in our families. It’s really a window into a typical Iranian household, which is priceless because no other book that I know of has been able to do that. I don't think he set out to do that. I think he did it unwittingly. I think he was just trying to write a great story.

There are so many other books. There are great works of literature but I wouldn't recommend them to someone who wants to learn the culture and history of the country. There is a great book called The Soul of Iran by Afshin Molavi and it's a travelogue, but it’s more than that. The guy is Iranian himself and he goes on a road trip round Iran. Each chapter pertains to a different city in Iran, and he really goes into the history of these places and into a lot of details that even I wasn't aware of at the time. It really gets into the nitty-gritty of things. It’s a wonderful introduction to Iran and its people for someone who doesn't have any knowledge of the place because there are lots of garbage ones written by Iranians, novels or memoirs written by Iranians in the West.

Here in Toronto if you go to your local bookstore the store is more or less the same when you are looking for novels or memoirs by Iranian authors. On the whole I’ve found that they tend to focus on the Iranian revolution. The story is always about some young woman who was living it up before the revolution with her parents and husband, and all of a sudden this Khomeini figure turns their lives upside down and they are forced to leave the country and take up residence in the States or in Europe and start up anew. It’s all about this one moment in history and how it ruined everything. Or it’s about someone who is tortured in prison, and how glad they are to have escaped miserable and loathsome Iran in one piece. Not to say that these stories aren’t true — I’m just kind of sick and tired of seeing them as the ones predominantly promoted and marketed in the West. But, of course, there are certain agendas at play here.

Going back to what I was saying, a lot of what I read is historical. I’m sort of wary about modern travelogues because in many cases the people writing these books have no credibility. They take a trip to Iran they spend a few days there and then write a book. But then, there are others like Afshin Molavi who write little gems.

Another book that's just come to my mind is Isfahan Is Half the World by Mohammad Ali Jamalzadeh. It’s a wonderful little book. It's hard to get a hold of because it’s out of print, but if you can find it, it’s lovely.

If there is one book you should read it’s The Shahnameh you can’t get better than that if you’re looking to understand Iran.

Luke: Going from Iranian literary heroes to Turkish ones, I really enjoyed your piece on Yaşar Kemal. I was having a discussion with another critic here in Turkey and he was posing the question of what people who don't know Turkey see in Yaşar Kemal. I was wondering if you have any thoughts about that?

Joobin: Well I don't really know Turkey as much as I do Iran.

Luke: That's exactly my point. For people like me and Turks we like Yaşar Kemal because he speaks to a part of the Turkish experience and he’s very important in the literary landscape of Turkey. I was curious to ask somebody who is outside of that what drew you towards him.

Joobin: The first book I read of him was İnce Memed, or Memed My Hawk as it’s known in English. Aside from the story I could really relate to the setting so much because Eastern Turkey and Iran at least on the surface share so many similarities. There is a writer, a giant of contemporary Iranian literature — Mahmoud Dowlatabadi. His novels also take place in rural settings and tell the lives of villagers. There are so many similarities. If you just drive from western Iran to eastern Turkey you won’t see that much of a change. Of course we are talking about different ethnicities, unless you’re talking about the Kurds, as well as different rituals, but in many cases it’s the same. It’s difficult to say what exactly is the same. I can’t quite put my finger on it. Everything was just so familiar to me; the scenes painted in his novels, these villagers who depended on one year’s cotton harvest for their livelihoods. So many parallels were drawn in my mind between his settings and characters and, let’s say, the novels of Dowlatabdi or even Iranian films. If you watch a film like The Cow, which is a classic, you’ll see what I mean. Everything is just so familiar. I didn't feel as an Iranian that it was particularly Turkish or unique to Turkey. I don't think Yaşar Kemal being Kurdish had anything to do with it but it certainly attracted me to him. For example, in İnce Memed, at least in the first two books –the only ones that have been translated- he never mentions if Memed is Turkish or Kurdish. You don't know his ethnicity. I always like to think that he was Kurdish. I always felt that there was this, sort of, bond between us because if he’s Kurdish it means we are of the same stock.

Just the settings of his novels like Çukurova in İnce Memed and also The Wind From the Plain, it was as if he were talking about the Iranian countryside. Like the Turks, the Iranians have largely been a nomadic people. This culture and way of life he [Yaşar Kemal] describes like cooking bread and picking cotton, the lives of the villagers, was as if he was talking about Iran. I really could identify with them. That's not to say I’ve lived in an Iranian village before or that I know what it’s like to live amongst Iranian nomads like the Bakhtiaris, who still make their annual migration, they've been doing so for a millennium. Nonetheless, there is something in Yaşar Kemal’s work that really resonated within me, in the innermost part of my being. It’s always difficult to put feelings into words but I feel this kinship with him.

Luke: The last thing I’d like to talk about is Reorient. Tell me how it started up and what was your aim with that?

Joobin: There was no aim really. As with most of the other things I do it was done on a whim. It was founded on a whim. It seemed like the natural thing to do to combine my two loves, well not my only loves because I have other loves, so a love for writing and this desire to have a publication with a love for, first and foremost, Iranian culture but also the culture of the region as a whole. I founded it and initially it had more of a blog feel to it and I was doing almost all of the writing. They were much shorter pieces, more like press releases at times, and soon after I started writing longer pieces, more exploratory pieces and the character, the nature of the publication really changed together with its direction. I think it was attractive to a lot of people and contributors started getting in touch with us expressing a desire to write an article. Soon, I found myself with a network of writers from all corners of the globe who were driving it. Of course I was more active in those days than I am now. If it hadn’t been for them it wouldn't have become what it is today. It was all very organic. There was a vision and mission of course, which was to change attitudes, as I was talking about earlier, and to introduce people to a lesser known side of the region, or at least one that is less frequently discussed in the west or outside the region. I really didn't know what I was doing and the publication didn't really have a voice of its own aside from me and my rock and roll references and all that but it found its voice after I wrote the long-form essays, experimental pieces, atmospheric pieces. My friends would read them and would say ‘I don't know what you’re getting at here.’ I would be inspired by a film. I would use, let’s say a Lebanese film, or an album of Iranian classical music, to get creative and go wild in an ambient piece of writing. So I was, most of the time, looking for excuses to write and I grew tired of writing those sort of dry and bland reviews that had a press release feel to them. Let's say you would go to an exhibition and just write about what you’ve seen and throw in a few references to other works of art or, as in the case of some other writers, French philosophers. That was really boring to me. I approached every piece I was writing as a piece of literature, creative writing of prose rather than an article. That was really when Reorient found its voice and I found my voice as a writer. The direction really changed and then when we created our social media accounts and started sharing on instagram images that we thought represented Reorient or found interesting. Things we would tweet or post on Facebook really helped define the brand and identity of the publication. There came a time when people would say that this reminds me of Reorient or things along these lines. Prior to, let’s say, early 2014, yes it was great, but there was nothing really distinguishing it from other publications, even though there still aren’t too many.

More and more contributors started pitching in and we could do things on a larger scale it was all very natural. I can’t say I had this in mind from day one because I didn't. It was something I wanted to do and it turned into this. Just like the stories in the book you write and write and write and write and after a certain point you realise that I have material for a book or see what you can do if you connect them in a certain way.

I don't know if that answers the question.

Luke: For sure. I definitely thought about your publication when I was developing Bosphorus Review as a positive example that I emulated in some respects.

Joobin: Thank you.

Luke: You got it. Am I right in saying that you are closing Reorient?

Joobin: For the time being at least because my focus is my books and other personal projects. So I write frequently for other publications like The New York Times or the Financial Times, the BBC and a slew of other publications. I write texts for artists' books, I’m commissioned to write pieces by various individuals, institutions and organisations. That is what my focus is on right now. I don’t know it’s just been over five years since I founded Reorient but I felt that, a few months ago, I needed to move on personally. I don't know if this is a permanent thing but for the time being at least it’s nice to take a break. Just only writing about the Middle East I felt like I’d been typecast, people only looked at someone who could write about the Middle East and couldn't write about other subjects like fashion or music or art that isn’t Iranian or isn’t Arab, or Turkish. That was also something that was bugging me. I think what was at the heart of this change was the desire to explore my other interests because, believe it or not, I’m not only interested in the Middle East or Iran. Iran will always be my number one love but there are so many other subjects that I’d like to write about, work with and explore. For example, rock and roll which was my first interest. I’m writing more about it now and it was in my second book, my first work of fiction. There are loads of references in With My Head in the Clouds. I find these things refreshing I have a lot more of a balance. That's not to say that I won’t write about the Middle East or Iran, there are just so many other things I'd like to write about and with Reorient it was becoming very time-consuming. I either do something right and give it the attention it needs or I don't do it at all. I don't feel that right now I can give it the attention that it deserves. Aside from that, I’d exhausted myself updating our social media accounts and everything. I really wanted to get away from that. I know our social media accounts are very popular but I don't really have the time for them.

I really don't know; I haven’t put an end to Reorient’s activities indefinitely but at least for the time being. I might revisit it in the future; it might take a different guise or form. I don't know right now, it’s only been a few months since I stopped writing or accepting any new contributions.

Luke: Fair enough. I understand that sentiment but I have to say, on a personal level, that I’m sad there won’t be any more Reorient.

Joobin: We have a huge archive and everything will still be there and accessible, many of the pieces do have that timeless quality to them. There are others by other contributors with still something to be gleaned from them even now and in the future. Even if we don't publish in the future there will always be this archive of material that other people can look and refer to for their own projects.

It will always be online. It will always be here. I hope it will be back but it depends on how I’m feeling.

Luke: My last question is one that I ask most people when I interview them: What are you reading right now?

Joobin: I’ll give you the name of a book that I recently read. It’s a novella called No Tomorrow by Vivant Denon. The story is only thirty-five pages and they have included the French text as well to beef it up a bit and an introduction. It’s really … dreamy.

Luke: Thank you so much for talking to us.

*

Next: