Review: Celestial Bodies, Jokha Alharthi

By Matt Hanson

Of all the layers of postcolonial trauma that the Arab world endures, caught between the Global North and South, anomalous and encompassing as the immemorial, transnational crossroads of its Middle Eastern region, none has lingered so stubbornly, or misleadingly as romantic love.

Roused by a paradisal persuasion and primordial passion for mysticism and poetry under the starry moonscapes of its vast deserts, the Arabian peninsula is home to a septet of nations who continue to brace the challenge of modernizing their sultanates and sheikdoms. Oman lies at its easternmost tip.

Jokha Alharthi wrote a gushing second novel whose soapy melodramas border on pulp. But through a nonlinear narrative of historical fiction, she adds fact and reason enough to hold runaway skepticism while preserving her vision. In illustrative, multiple first-person prose translated by Marilyn Booth, she tackles slavery, immigration, divorce, and a murder mystery.

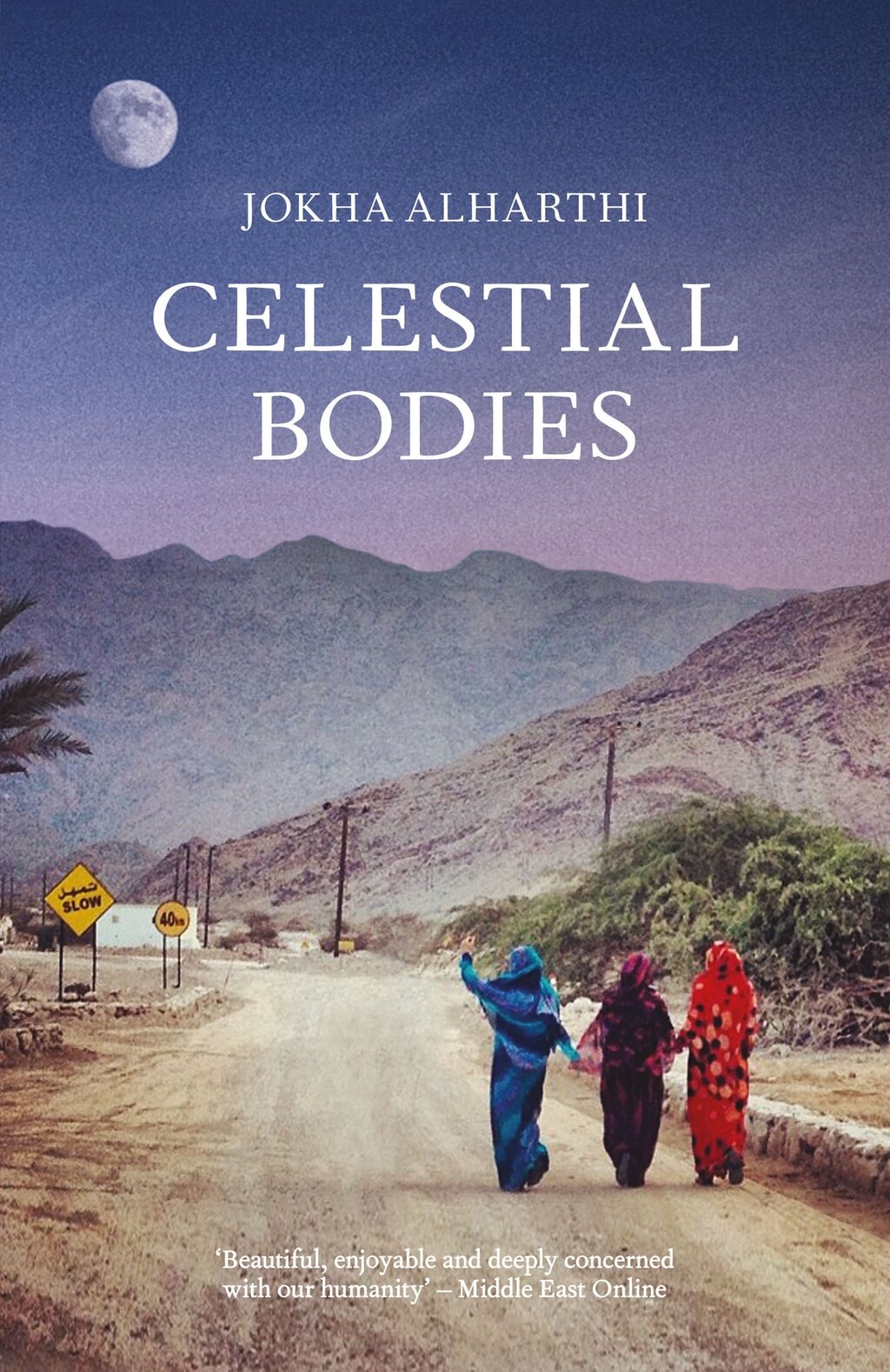

Celestial Bodies won the 2019 International Man Booker Prize, besting the only male shortlisted, Juan Gabriel Vásquez, and the past year’s recipient Olga Tokarczuk. Since its inaugural 2005 award went to Ismail Kadare, an Albanian novelist whose historical fiction also explores remoteness in Islamic lands, it is the first time a book written in Arabic has won.

Originally published as “Ladies of the Moon” (Sayyidat al-qamar) in 2010, the multigenerational family saga revolves around three granddaughters of a prominent sheikh: Mayya, a young mother, Asma, an introspective bookworm, and Khawla, a beauty queen.

In the opening passages, Mayya pines for true love over her sewing machine. But she quickly marries.

Her husband, Abdallah, the son of a merchant, is to a great extent, the sun of the novel’s solar system, around which the many characters of Celestial Bodies circle like planets feeding off the steady rays of his monologic, emotional reflections. On a flight to Europe, his chapters root over a century of nonconsecutive events in the stunted growth of an Omani family tree.

Mayya is a casualty of unrequited prayers. Once betrothed, her virgin longing diminishes and is left undeveloped. It is only expressed indirectly, in Abdallah’s solitary ruminating, how she put her youthful optimism to bed. Alharthi eloquently explained, “once branded by childbearing, a mother’s embrace could no longer be a lover’s embrace.”

All sense of hope is planted in the succeeding generation, epitomized by naming her firstborn London. In scenes apt for daytime Arab television comedy, salons of married cousins, gossiping aunts and religious uncles scandalize the decision. Abdallah faithfully protects his wife and their daughter.

It is arguably in the voice of Abdallah where Alharthi’s literary empathy shines brightest in Celestial Bodies. Her writing about women is as honest as it is pitiless. But for men, she writes internal drama with a surprisingly disarming poignance. He is a motherless child, raised by his father’s slave, Zarifa, a principal character.

Oman did not abolish slavery until 1970. Born in 1978, Alharthi is among the earliest generation of Omanis raised without slaves. Celestial Bodies contemplates this epochal rift in human rights through social, economic and also religious lenses. She returns to the source, telling of how Abdallah’s grandfather became rich from the slave trade.

About halfway through the novel, a slave named Ankabuta, meaning Spider-Girl, cut the umbilical cord of Zarifa from her womb with a rusty knife. She cried, not because she had given birth alone, or because she had been impregnated by force, but because she had to wrap her dirty head scarf around her newborn and it was her sole possession.

It also happened to be the 25th of September, 1926 when the Slavery Convention in Geneva criminalized the sale and trade of people around the world. But she lived in the backwater Omani village of al-Awafi, where, until his dying day, the son of her owner, Sulayman, was unrelenting: “What does the government have to do with any of this? My slave, mine.”

Sulayman and Zarifa are partial to a subplot that sends Abdallah spinning with the prospect of an unmentionable truth, that his mother, Fatima, was murdered. It is one of many narrative metaphors for love and slavery, posed as parallel forms of human ownership. Alharthi deftly mirrors the greater geopolitical context of Arab dependency on the English-speaking world.

“My Arab country, where restaurants, hospitals and hotels all announced that ‘only English is spoken here’, Abdallah laments, embarrassed because he is a businessman who does not speak the world’s lingua franca. His shame is echoed when he remembers a day at school when everyone proudly announced their father’s occupation. His being a merchant was ungodly.

Mayya’s parents are equally disillusioned by matrimony. Her father, Azzan, has an amorous affair with a Bedouin woman named Najiya. To him, she is The Moon. Alharthi styles some of the most spectacular prose in her novel describing Najiya’s beauty, immersed in the ancient Arabian landscape among its indigenous, nomadic camel-herders.

Celestial Bodies is a treatise on the contemporary Arabic novel in unbroken continuity with its literary heritage. The preliterate, oral culture preceding Islam is celebrated, with liberal references to proverbs, the legend of Layla and Majnun, the classical Iraqi bard al-Mutanabbi, and the 19th century Omani poet Abu Muslim al-Bahlānī who died in Zanzibar in 1920.

Although an academic, Alharthi does not write dryly. She is a fine humorist. When the first car is introduced to al-Awafi, the elderly mother of the sheikh who owns it throws a rock at it, breaking a window and cursing it as “the work of the Devil”. Before their weddings, a local widow tells Asma and Khawla how she initially battered her kind husband to preserve her dignity.

But ultimately, Celestial Bodies is a tearful tale about dependency and the mutual trauma of all involved. Muhammad, the third child of Abdallah and Mayya, is autistic. His weight is the straw that breaks the camel’s back. Alharthi describes Abdallah in another proverb as “a man who’s not in the caravan nor in the warring band”. He struggles to be Omani, a father, human.

*

Next: