The Sultan Across the Golden Horn: An Ode

By Sultan Mehmet Fatih, aka Avnî

Translated by Selim Güngörürler

A sun-faced angel, the moon of the universe, saw I

Those dark hyacinths of his are the lovers’ sigh.

Like the shining moon, that coy cypress has dressed in blacks

It turns out, he is the king-in-beauty of the realm of the Franks.

Whoever does not set heart on his monkish girdle’s knot

is a heretic among lovers, from the folk of faith he is not.

To those whom his dimple kills, his lips revitalize

That soul-bestower’s way is Jesus’s religion, I surmise.

There [in Galata] I saw him, named Jesus, and Frankish-mannered

Whoever saw Jesus would say “by his lips is He resurrected.”

Do not fancy that the bonnie one submits to you, o Avnî

The king of Istanbul you are, and the king of Galata is he.

Latin Transcription:

Bir güneş yüzlü melek gördüm ki âlem mâhıdır

Ol kara sümbülleri âşıkların âhıdır

Karalar giymiş meh-i tâbân gibi ol serv-i nâz

Mülk-i Efreng’in meğer kim hüsn içinde şâhıdır

Ukde-i zünnârına her kimse kim dil bağlamaz

Ehl-i îmân olmaz ol âşıkların güm-râhıdır

Gamzesi öldürdüğüne lebleri cânlar verir

Vâr-ise ol rûh-bahşın dîn-i Îsâ râhıdır

Bir Firengî şiveli Îsâ’yı gördüm onda kim

Lebleri dirisidir der idi Îsâ’yı gören *

Avniyâ kılma gümân kim sana râm ola nigâr

Sen Istanbul şâhısın ol[da] Galata şâhıdır

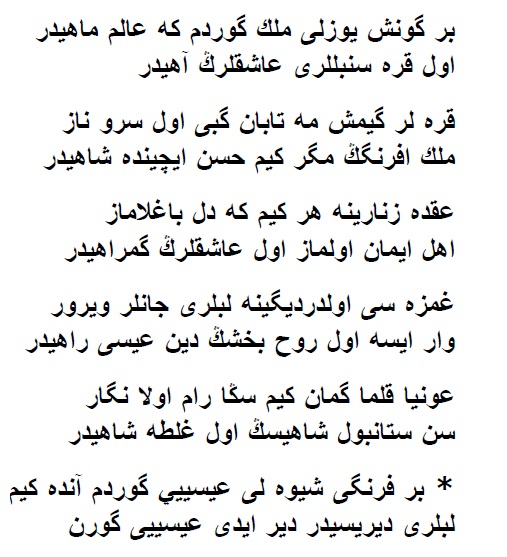

Ottoman Original:

Translator’s Note

Mehmed II (r. 1451-1481) – known as the Conqueror due to his conquests of Constantinople, central & northwestern Anatolia, Greece, Albania, Bosnia, Genoese colonies around the Black Sea, Aegean islands, and acknowledged as the founder of an empire from the existing Ottoman realms – was not only an able field marshal and ruler, but also an exceptional intellectual even for his contemporaries in Renaissance Europe and the Middle East which was living out the last gleam of its medieval progressiveness in science and thought. A polyglot, he read scientific and literary classics in Greek, preferred Arabic as the orient’s academic lingua franca, conversed with Italian diplomats and courtiers in Latin, recited Persian epics from memory, and learned Serbian from his close entourage, all in addition to his native Turkish. Philosophy, comparative theology, literature, history, antiquities, and painting were among his interests, which he cultivated at his court manned by oriental professors, ex-Byzantine scholars, and Italian humanists, whom he actively promoted to debate, compose, translate, and research. Apart from the histories narrating his life, the works he patronized and the collection at his personal library are extant material witnesses to his intellectual caliber.

As a poet, he used the penname Avnî, i.e. “of help.” His compendium of Turkish poetry, to which the translated ode also belongs, features pieces that are less overwhelmed by Arabo-Persian artistic and linguistic elements in comparison to the post-fifteenth-century Turkish court literature. His poetical accomplishment may not be on a par with those of Necâti Bey or Ahmed Pasha, who were attendees at his court and who, by general consensus, are among the all-time bests of Turkish literature, but still, Mehmed II’s poems offer an enjoyable read for their clarity and neatness in expression as well as the possibility of linking some of his lines with potential real life experiences of this outstanding historical figure. With regard to the translated poem, the reader might find it interesting that the sultan is known to have enjoyed making excursions to Galata for entertainment, such as his participating in a feast given by a Florentine merchant in his honor and his reported visits to observe church rituals. Like in this piece, Mehmed II’s verse occasionally uses Istanbul as scene and Istanbulites as characters.

For many oriental court poets, there have been arguments, both at academic and popular levels and with an ever-increasing vulgarization, on whether the portrayed subjects are to be taken metaphorically or literally. While the possibility of allegory shall never be ruled out, many poems do feature references that make it impossible to interpret them non-literally, such as in Mehmed II’s two quadrants of declaration of love to a certain Hasan Bal. Yet, the here-translated ode leaves room for interpretation in either way.

Selected Further Readings:

Fâtih Dîvânı ve Şerhi. Edited by M. Nur Doğan, Yelkenli Yayınevi, 2007.

Şengör, M. Celâl. “Kitaplarının ve Entelektüel İlgilerinin Işığında Fâtih Sultan Mehmed II.” In Klaudios Ptolemaios: Coğrafya El Kitabı, Boyut Yayıncılık, 2017.

Tekin, Gönül. “Fâtih Devri Türk Edebiyatı.” In İstanbul Armağanı: Fâtih ve Fetih, İBB Yayınları, 1995.

*

Born in Izmir, Selim Güngörürler obtained his PhD from Georgetown University. After working in Washington DC, Vienna, and Berlin, he is currently employed at Boğaziçi University as researcher. Although he studies and publishes on diplomatic history, he is on a constant lookout for time and opportunities to put to use his fondness for literature, particularly Persian and Turkish poetry. He is concerned that eventually, his urge to read, teach, and translate verse might also claim the time with which he makes a living from historiography.

Next: